How to present a recommendation

A follow-up to How to use the MECE framework.

My first consulting success was down to pure luck. If I had been collaborating with any other client, it would’ve gone the other way. The point of contact was a woman handling digital marketing for a SaaS startup. She was a direct communicator — an all-around effective individual.

Her company had provisionally signed off on a one-month engagement. Our goal was to create a digital marketing strategy for the upcoming year. If the powers that be approved this strategy, they would extend their commitment to Distilled for a full year. We would put the plan into action together.

Now, I had prepared for this project. Even before the kickoff, I assembled all the data I could. And after, I followed up with the client team for a qualitative angle. A towering hierarchy of spreadsheets, diagrams, and summaries enumerated all the relevant facts I had collected.

In four weeks, I put together what I thought was a winning plan. It centered on a new content strategy. This content strategy would position the client as empathetic to, and inclusive of, their most likely growth market.

The deadline for delivery arrived. I sat down with the client (virtually — she preferred Skype) and revealed to her my recommendations and approach. The key to my presentation was a diagram (I preferred Visio) visualizing my strategy. I used every minute of that hour. No detail of my vision was left out.

To my lasting horror, the point of contact was unimpressed with my diagram. She didn’t criticize my recommendations or methodology. But she did tell me that she hadn’t got what she was looking for. She wanted a report — in full prose.

She even went so far as to outline the document. It was a straightforward narrative that walked through how I’d come to my conclusion. I thought: I’ve done all this research. I’ve made a recommendation. Isn’t writing this down a waste of time?

Still, I prepared everything exactly as she suggested. I delivered it to the client with low expectations of success. But something about that report worked. After brief deliberations, her company signed on for a year of work with Distilled. We coached them as they experimented with a new content strategy. Years later the company has tripled down on that content. They’ve evolved so that — unless you were there — it would be hard to see the kernel from which their strategy grew.

When that year was up, and our relationship drew to an end, I reflected on how we’d got there. Here’s that report in my left hand; here’s the mass of research in my right. I saw that it wasn’t enough that I found a solution. To change the client’s approach, I had to take her on that journey of discovery, too. I needed to show her so that she saw the problem as I saw it.

I was lucky to have a client who could help me see her point of view — to paint a clear picture for me. She clarified what she needed to understand to make things happen. I asked myself: How can I apply this lesson to my other clients?

The Effecting Change series has a shared thread: how do we convince a client to change? The last post showed how to discover a plausible alternative action. Once you have it, you must share it with the client. This post is an answer to the question:

How can I make a recommendation so that the client follows it?

We’ll introduce a simple three-step process: suggest, demonstrate, and elaborate. This method can be applied to any recommendation you make.

>> Open deck in Google Docs <<

This example deck covers a trivial technical problem — Distilled’s site links to URLs that return a 404 status code.

The client must choose to act

The point of a consulting engagement is for the client to do what they otherwise would not have done. Their action is what’s at stake. That’s the nature of the relationship — clients have the power to choose, and the consultant has the power to advise.

In general, people do what they want.

The client will only follow your advice if it reflects their own desires. There are two ways we can frame the client’s choice of action. We can ask either of these questions:

- Why doesn’t the client do what I say? or

- Why doesn’t the client want to do what I think they should?

The first option is no option at all. The client is not obligated to take orders. Framing the conversation this way is patronizing.

The second question is more to the point. If the client doesn’t want to act differently, then what we recommend will not happen.

The client may resist your solution

Let’s assume the client wants to see their problem solved. (This is not always the case!) That still does not mean they want your solution to be realized. Why not?

The act of hiring a consultant may make the client feel vulnerable. On some level, hiring an outside expert in an admission that, “I need help.” If we don’t respect that, the client won’t respect our ideas. There’s nothing morally wrong with this — it’s human nature. If we walk into a client meeting brimming with pride in our work, there is no grace in that.

The client has the right to fail

The responsibility for choosing what to do lies with the client. They have to live with the consequences of their choices, while the consultant gets to move on to the next project.

It is possible the client will make a decision you do not approve of. That’s OK. Your job is to do everything you can to help the client succeed. It is not to ensure that the client doesn’t fail.

Three steps: suggest, demonstrate, elaborate

Let’s recap. We’ve seen that our goal is to change the client’s choice of action. We understand that the client has a reason to feel vulnerable. And we accept that the client has the right to their own position.

In the face of this reality, you have one advantage to lean on. You know your advice is good. You know this because it represents what you would do in the client’s shoes. If you’re recommending something you wouldn’t truly want to see happen, that’s sad.

Under these conditions, it’s irrelevant whether the client acknowledges that your recommendation is right. They only need to see your solution the way you do. When they do, they might choose to adopt it.

How do we take the client on this journey with us? Here’s my three-step process:

- Suggest. Paint a clear picture of how things are.

- Demonstrate. Tell your audience how you react when confronted with such a picture.

- Elaborate. Explain why your reaction is reasonable.

Following these steps, in this order, you dramatize your response to the problem. Seeing that, the client can emulate your action. They not only hear your response, they have your response.

Let’s walk through the three steps. I’ll show how each of them gives the client the opportunity to come up with your recommendation under their own steam.

The example deck follows this pattern for a trivial technical problem.

>> Open deck in Google Docs <<

First, suggest — paint a clear picture

Start by presenting a clear picture of what is happening:

- “Googlebot has to crawl a million thin pages to find your one thousand pages of indexable content.”

- “Your legal team requires four weeks to approve an email campaign.”

- “The internal time tracking system can take up to twenty seconds to switch tasks. The team reports that they avoid reporting entirely when the perceived effort outweighs the cost of inaccurate tracking.”

Peter Block says in Flawless Consulting that presenting a clear picture is about 70% of the consultant’s job. I agree. No matter how well your client understands the problem, your presence provides clarity that they did not have before. Something about what you see will be new to them — otherwise, why are you necessary?

The picture is the first opportunity for the client to begin emulating your behavior. Clarity is crucial. By posing the problem clearly, you are implicitly suggesting possible solutions.

Before you joined the conversation, the client didn’t see what they were supposed to be responding to. But once they see the real problem, they’ll spontaneously make first attempts at a solution. Someone in the room says:

- “I see. If we make the time tracking system faster, we’ll get more accurate data,” or

- “Those million pages result from our approach to faceted navigation. We need to rethink how we link to those pages.”

If that happens, don’t let the opportunity slip away from you. Seize those ideas and encourage them, whether or not they fit with your recommendation. After all, the client is more invested in the fix than you are! If they can commit to a solution of their own devising, so much the better.

And if there’s silence in the room — what then? By revealing the scope and nature of the problem, you may have plunged your audience into anxiety. Heads will nod as suspicions are confirmed. Gears start to turn as they grasp for a solution. They look to you for an answer. What happens next?

Next, demonstrate — offer a plausible alternative action

Maybe the client doesn’t see the solution immediately. That’s OK. We all come to the table with different experiences. Even an expert team hasn’t encountered every situation before. To share your experience with them, you must now demonstrate what you would do in their shoes.

You will not tell the audience what to do. You won’t even tell them what to think. You will model the behavior you want them to emulate. You will say, “When I am faced with a problem like this, here is what I do.”

This attitude transforms the conditions for success. If you think your job is to give the client a solution that is crystalline in its perfection, the bar you’ve set for yourself is impossibly high. It’s all or nothing. If the client rejects your solution, they reject you. Your consultation has had no value.

But when your job is to show the client how you would choose to act, that’s no longer the case. The burden lifts, your anxiety evaporates. Even if the client doesn’t follow your recommendation, you will still have contributed to the conversation.

Demonstration is the second chance for the audience to emulate your response. Seeing the picture, and what you would do about it, they may say, “Yes, I can see why you want to do this. We should do that, too.” And your work is done — skip the rest of the presentation if you like.

If the audience does not immediately accept your solution, you have entered the final stage. Prepare yourself for the utmost exertion of your empathy and discipline. Because an unease will grip the room. The audience is pensive. They fidget. Finally, someone says, “Can it be that easy?” or “Will it really require that much effort?” You may see uncertainty, denial, or mistrust. Don’t give up. You’re almost there!

Finally, elaborate — explain how you came to think this way

The audience has seen their problem, and they have seen a solution. If they have not accepted the recommendation, then they are resisting it, consciously or not.

It may be that:

- They don’t understand. Specifically, they don’t see the link between what is wrong, and what you want to do about it.

- They are embarrassed. The solution seems simple. Why didn’t they see it?

- The solution is inconvenient. It comes with political challenges — maybe they have seen the answer and are in denial.

In this case, we need to elaborate on why our suggested response to the situation is not only plausible but warranted. Take the client through your thought process, all the way to its conclusion.

Preparation counts. Understand your audience before you present. When talking about a technical change, you may need to walk through methodology and rationalize your decision-making process. In other cases, the client will want to hear about how doing this will help them beat their competitors. One size does not fit all.

With that completed, you have done your job. You have suggested possible solutions by painting a clear picture of the problem. You have demonstrated an appropriate response. And you have elaborated upon this by providing further justification. The client may choose to change, or they may not, but you have done everything possible to help them succeed.

Twenty minutes or less

Now, do all of that in twenty minutes.

In the introduction to this post, I mentioned that my ill-prepared presentation took an entire hour. This was another mistake on my part. For an hour-long session, your part shouldn’t take more than twenty minutes. The client’s response to your recommendation is more important than what you recommend. The more you talk, the less you’ll hear.

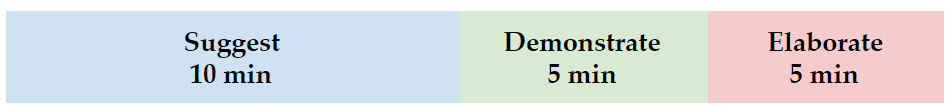

A reasonable breakdown might be:

These timings include a generous allotment of time for client reactions and questions, so don’t assume you have all twenty minutes.

Note that suggestion is longer than demonstration and elaboration. By the time you get to demonstration, the audience will have anticipated your solutions. By the time you’ve thoroughly explained your demonstration, they may not even need to hear your elaboration.

For a full breakdown of how such a meeting should be scheduled, I highly recommend Flawless Consulting by Peter Block. This book gives down-to-the-minute timings (which, I admit, my suggestion here deviates from).

Practice makes permanent

I have found success by using this strategy. So have the colleagues I’ve shared it with — I’m particularly proud of some of the work Sergey Stefoglo has done. You can do this, too.

I’ve seen consultants refuse to learn from their experiences, banging their heads against a wall in frustration. Don’t let that frustration become so frequent that you assume it’s a natural condition. It isn’t. An effective, trusting relationship with a client is possible.

Practice this technique in every recommendation you give — not just the ones that count. I was lucky to find a client that gave me the feedback I needed in order to improve. You have that opportunity as well. Don’t waste it.

As for me, with all of the variables that go into a successful engagement, I still count myself lucky if a project goes well. But these days, somehow I’m feeling lucky more often.

>> Open deck in Google Docs <<

Engage

If you want to continue leveling-up your consulting skills, I have two resources to recommend.

First, Kindra Hall’s SearchLove presentations. Kindra’s teaches the power of story in every situation, and techniques for improving your storytelling ability. The skills are invaluable in painting a clear picture for your audience. Kindra has spoken at our SearchLove events, and I’ve arranged for videos of her presentations to be freely available for readers of this post. Please watch her SearchLove San Diego 2015 or SearchLove Boston 2016 performances. You’ll need to sign up for a free Distilled account to view the whole session. Here’s a teaser to motivate you:

And second, Flawless Consulting by Peter Block. This is a book with great ideas in it, but it takes some effort to parse. I’ve created an internal training course for our team to share its principles in a more structured way. For those who are willing to invest in its ideas, there is the potential for a huge payoff. I’ve been working in the suggest, demonstrate, elaborate framework for a while, but Block’s ideas on structuring meetings for action have still helped me get more out of the client when I ask them to come to the table.