How to rank for head terms

Over the last few years, my mental model for what does and doesn’t rank has changed significantly, and this is especially true for head terms – competitive, high volume, “big money” keywords like “car insurance”, “laptops”, “flights”, and so on. This post is based on a bunch of real-world experience that confounded my old mental model, as well as some statistical research that I did for my presentation at SearchLove London in early October. I’ll explain my hypothesis in this post, but I’ll also explain how I think you should react to it as SEOs – in other words, how to rank for head terms.

My hypothesis in both cases is that head terms are no longer about ranking factors, and by ranking factors I mean static metrics you can source by crawling the web and weight to decide who ranks. Many before me have made the claim that user signals are increasingly influential for competitive keywords, but this is still an extension of the ranking factors model, whereby data goes in, and rankings come out. My research and experience are leading me increasingly towards a more dynamic and responsive model, in which Google systematically tests, reshuffles and refines rankings over short periods, even when sites themselves do not change.

Before we go any further, this isn’t an “SEO is dead”, “links are dead”, or “ranking factors are dead” post – rather, I think those “traditional” measures are the table stakes that qualify you for a different game.

Evidence 1: Links are less relevant in the top 5 positions

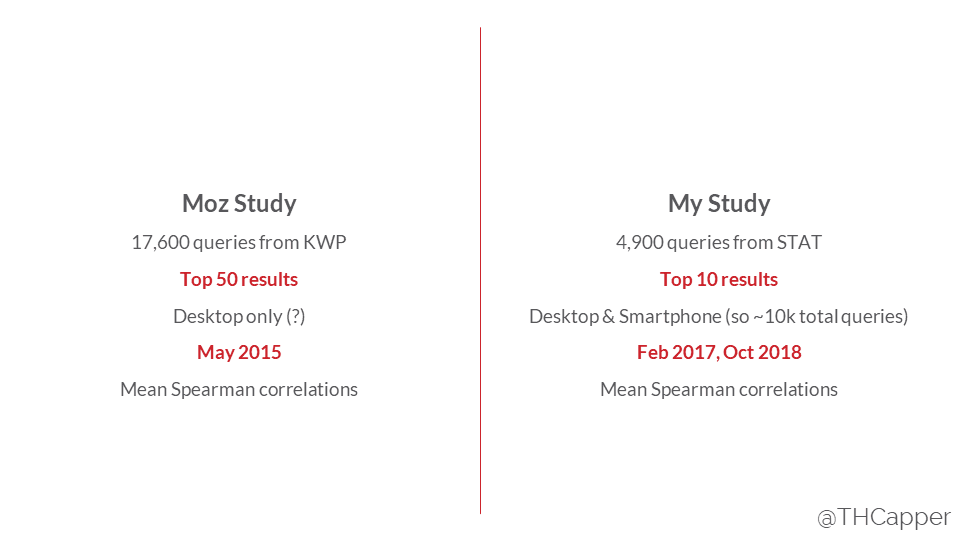

Back in early 2017, I was looking into the relationship between links and rankings, and I ran a mini ranking factor study which I published over on Moz. It wasn’t the question I was asking at the time, but one of the interesting outcomes of that study was that I found a far weaker correlation between DA and rankings than Moz had done in mid-2015.

The main difference between our studies, besides the time that had elapsed, was that Moz used the top 50 ranking positions to establish correlations, whereas I used the top 10, figuring that I wasn’t too interested in any magical ways of getting a site to jump from position 45 to position 40 – the click-through rate drop-off is quite steep enough just on the first page.

Statistically speaking, I’d maybe expect a weaker correlation when using fewer positions, but I wondered if perhaps there was more to it than that – maybe Moz had found a stronger relationship because ranking factors in general mattered more for lower rankings, where Google has less user data. Obviously, this wasn’t a fair comparison, though, so I decided to re-run my own study and compare correlations in positions 1-5 with correlations in positions 6-10. (You can read more about my methodology in the aforementioned post documenting that previous study.) I found even stronger versions of my results from 2 years ago, but this time I was looking for something else:

Domain Authority vs Rankings mean Spearman correlation by ranking position

The first thing to note here is that these are some extremely low correlation numbers – that’s to be expected when we’re dealing with only 5 points of data per keyword, and a system with so many other variables. In a regression analysis, the relationship between DA and rankings in positions 6-10 is still 98.5% statistically significant. However, for positions 1-5, it’s only around 41% statistically significant. In other words, links are fairly irrelevant for positions 1-5 in my data.

Now, this is only one ranking factor, and ~5,000 keywords, and ranking factor studies have their limitations.

However, it’s still a compelling bit of evidence for my hypothesis. Links are the archetypal ranking factor, and Moz’s Domain Authority* is explicitly designed and optimised to use link-based data to predict rankings. This drop off in the top 5 fits with a mental model of Google continuously iterating and shuffling these results based on implied user feedback.

*I could have used Page Authority for this study, but didn’t, partly because I was concerned about URLs that Moz might not have discovered, and partly because I originally needed something that was a fair comparison with branded search volume, which is a site-level metric.

Evidence 2: SERPs change when they become high volume

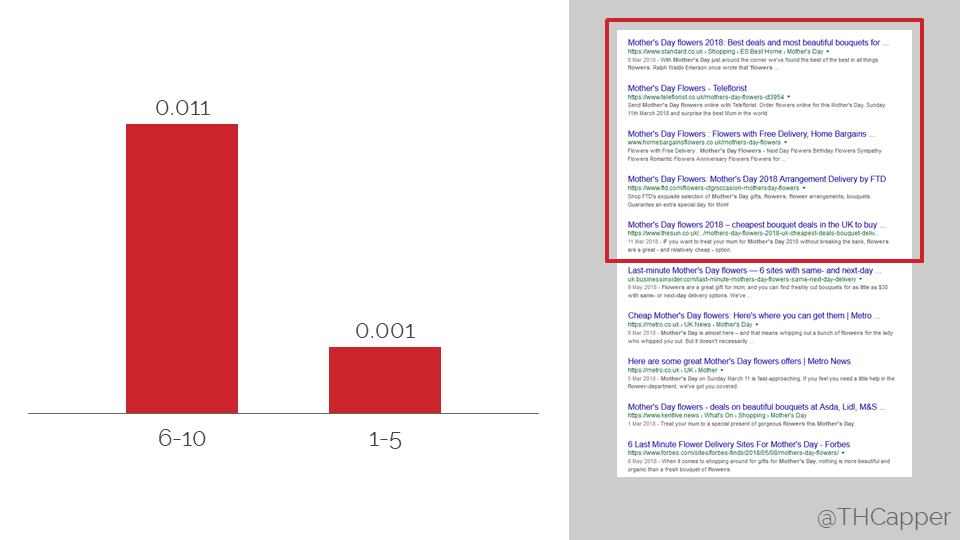

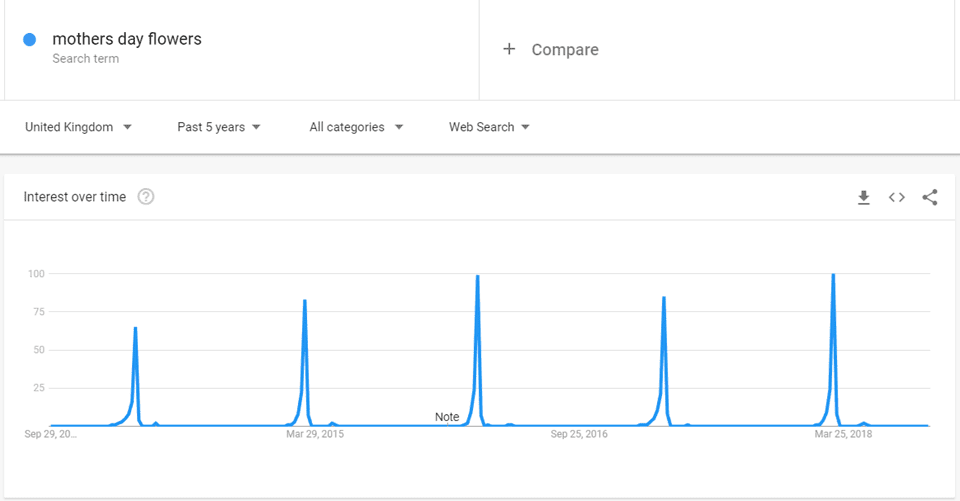

This is actually the example that first got me thinking about this issue – seasonal keywords. Seasonal keywords provide, in some ways, the control that we lack in typical ranking factor studies, because they’re keywords that become head terms for certain times of the year, while little else changes. Take this example:

This keyword gets the overwhelming majority of its volume in a single week every year. It goes from being a backwater search term where Google has little to go on besides “ranking factors” to a hotly contested and highly trafficked head term. So it’d be pretty interesting if the rankings changed in the same period, right? Here’s the picture 2 weeks before Mother’s Day this year:

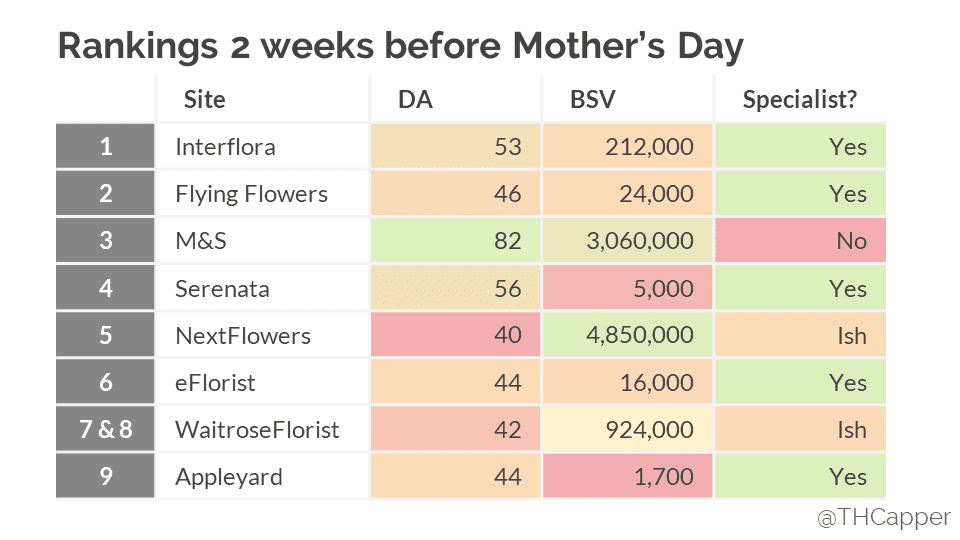

I’ve included a bunch of factors we might consider when assessing these rankings – I’ve chosen Domain Authority as it’s the site-level link-based metric that best correlates with rankings, and branded search volume (“BSV”) as it’s a metric I’ve found to be a strong predictor of SEO “ranking power”, both in the study I mentioned previously and in my experience working with client sites. The “specialist” column is particularly interesting, as the specialised sites are obviously more focused, but typically also better optimised. M&S (marksandspencer.com, a big high-street department store in the UK) was very late to the HTTPS bandwagon, for example. However, it’s not my aim here to persuade you that these are good or correct rankings, but for what it’s worth, the landing pages are fairly similar (with some exceptions I’ll get to), and I think these are the kinds of question I’d be asking, as a search engine, if I lacked any user-signal-based data.

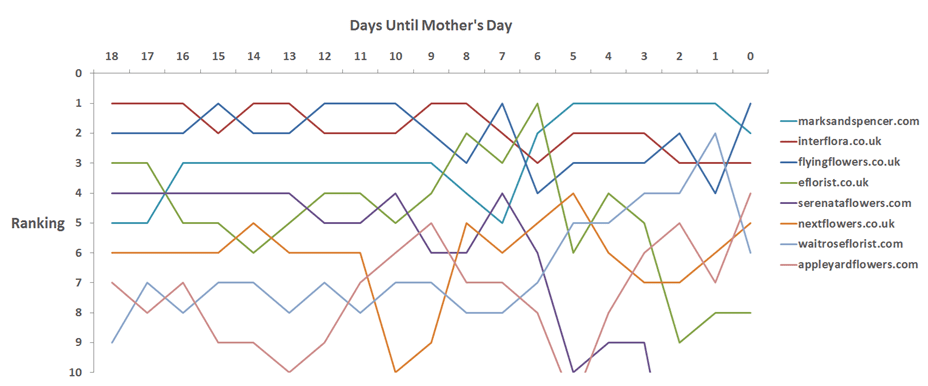

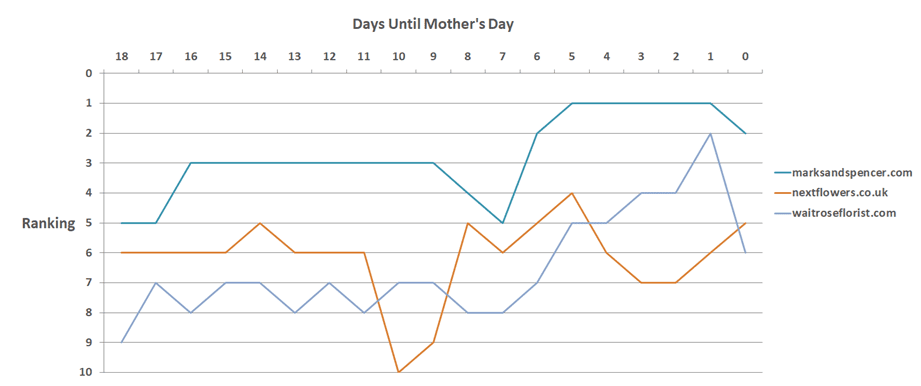

Here’s the picture that then unfolds:

Notice how everything goes to shit about seven days out? I don’t think it is at all a coincidence that that’s when the volume arrives. There are some pretty interesting stories if we dig into this, though. Check out the high-street brands:

Not bad eh? M&S, in particular, manages to get in above those two specialists that were jostling for 1st and 2nd previously.

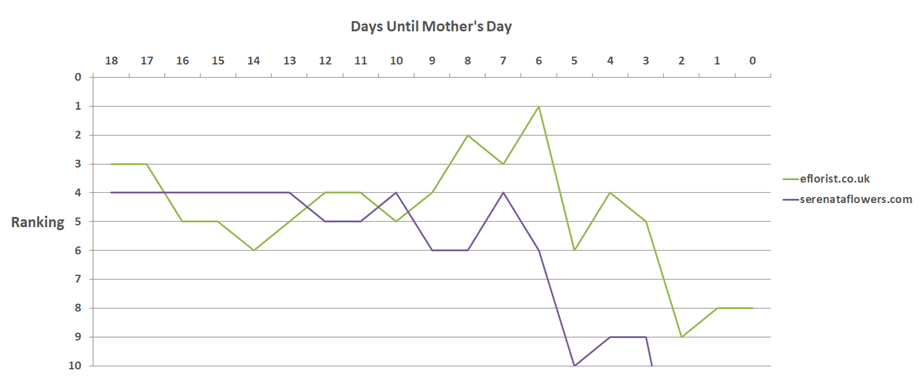

These two specialist sites have a similarly interesting story:

These are probably two of the most “SEO’d” sites in this space. They might well have won a “ranking factors” competition. They have all the targeting sorted, decent technical and site speed, they use structured data for rich snippets, and so on. But, you’ve never heard of them, right?

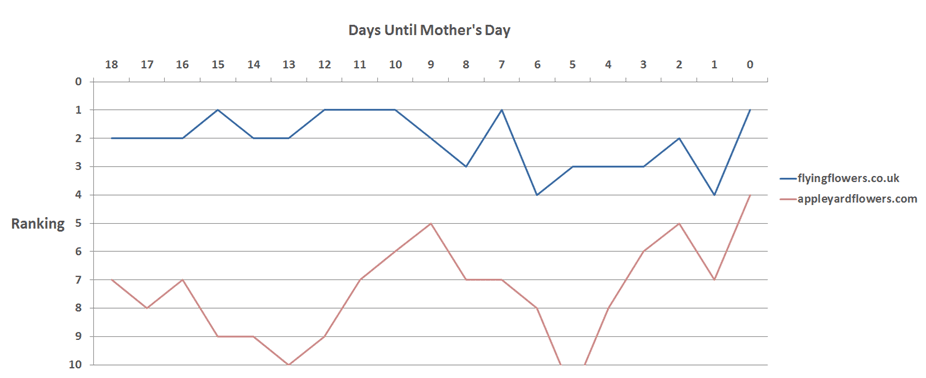

But there are also two sites you’ve probably never heard of that did quite well:

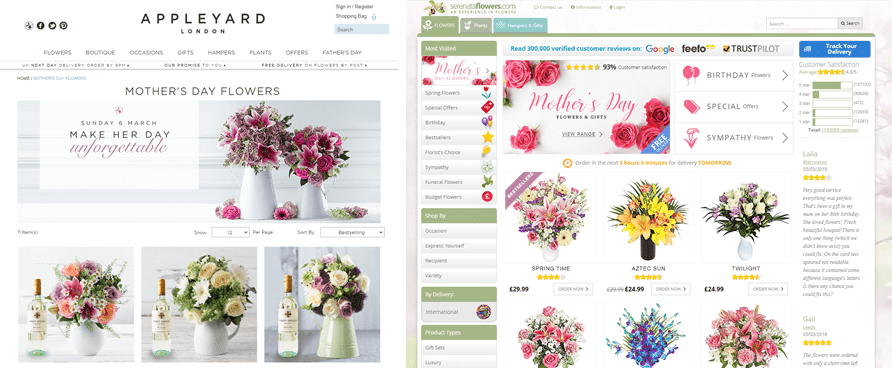

Obviously, this is a complex picture, but I think it’s interesting that (at the time) the latter two sites had a far cleaner design than the former two. Check out Appleyard vs Serenata:

Just look at everything pulling your attention on Serenata, on the right.

Flying Flowers had another string to their bow, too – along with M&S, they were one of only two sites mentioning free delivery in their title.

But again, I’m not trying to convince you that the right websites won, or work out what Google is looking for here. The point is more simple than that: Evidently, when this keyword became high volume and big money, the game changed completely. Again, this fits nicely with my hypothesis of Google using user signals to continuously shuffle its own results.

Evidence 3: Ranking changes often relate more to Google re-assessing intent than Google re-assessing ranking factors

My last piece of evidence is very recent – it relates to the so-called “Medic” update on August 1st. We work with a site that was heavily affected by this update – they sell cosmetic treatments and products in the UK. That makes them a highly commercial site, and yet, here’s who won for their core keywords when Medic hit:

| Site | Visibility | Type |

| WebMB | +6.5% | Medical encyclopedia |

| Bupa | +4.9% | Healthcare |

| NHS | +4.6% | Healthcare / Medical encyclopedia |

| Cosmopolitan | +4.6% | Magazine |

| Elle | +3.6% | Magazine |

| Healthline | +3.5% | Medical encyclopedia |

So that’s two magazines, two medical encyclopedia-style sites, and two household name general medical info/treatment sites (as opposed to cosmetics). Zero direct competitors – and it’s not like there’s a lack of direct competitors, for what it’s worth.

And this isn’t an isolated trend – it wasn’t for this site, and it’s not for many others I’ve worked with in recent years. Transactional terms are, in large numbers, going informational.

The interesting thing about this update for this client, is that although they’ve now regained their rankings, even at its worst, this never really hit their revenue figures. It’s almost like Google knew exactly what it was doing, and was testing whether people would prefer an informational result.

And again, this reinforces the picture I’ve been building over the last couple of years – this change is nothing to do with “ranking factors”. Ranking factors being re-weighted, which is what we normally think of with algorithm updates, would have only reshuffled the competitors, not boosted a load of sites with a completely different intent. Sure enough, most of the advice I see around Medic involves making your pages resemble informational pages.

Explanation: Why is this happening?

If I’ve not sold you yet on my world-view, perhaps this CNBC interview with Google will be the silver bullet.

This is a great article in many ways – its intentions are nothing to do with SEO, but rather politically motivated, after Trump called Google biased in September of this year. Nonetheless, it affords us a level of insight form the proverbial horse’s mouth that we’d never normally receive. My main takeaways are these:

- In 2017, Google ran 31,584 experiments, resulting in 2,453 “search changes” – algorithm updates, to you and me. That’s roughly 7 per day.

- When the interview was conducted, the team that CNBC talked to was working on an experiment involving increased use of images in search results. The metrics they were optimising for were:

- The speed with which users interacted with the SERP

- The rate at which they quickly bounced back to the search results (note: if you think about it, this is not equivalent to and probably not even correlated with bounce rate in Google Analytics).

It’s important to remember that Google search engineers are people doing jobs with targets and KPIs just like the rest of us. And their KPI is not to get the sites with the best-ranking factors to the top – ranking factors, whether they be links, page speed, title tags or whatever else are just a means to an end.

Under this model, with those explicit KPIs, as an SEO we equally ought to be thinking about “ranking factors” like price, aesthetics, and the presence or lack of pop-ups, banners, and interstitials.

Now, admittedly, this article does not explicitly confirm or even mention a dynamic model like the one I’ve discussed earlier in this article. But it does discuss a mindset at Google that very much leads in that direction – if Google knows it’s optimising for certain user signals, and it can also collect those signals in real-time, why not be responsive?

Implications: How to rank for head terms

As I said at the start of this article, I am not suggesting for a moment that the fundamentals of SEO we’ve been practising for the last however many years are suddenly obsolete. We’re still seeing clients earn results and growth from cleaning up their technical SEO, improving their information architecture, or link-focused creative campaigns – all of which are reliant on an “old school” understanding of how Google works. Frankly, the continued existence of SEO as an industry is in itself reasonable proof that these methods, on average, pay for themselves.

But the picture is certainly more nuanced at the top, and I think those Google KPIs are an invaluable sneak peek into what that picture might look like. As a reminder, I’m talking about:

- The speed with which users interact with a SERP (quicker is better)

- The rate at which they quickly bounce back to results (lower is better)

There are some obvious ways we can optimise for these as SEOs, some of which are well within our wheelhouse, and some of which we might typically ignore. For example:

Optimising for SERP interaction speed – getting that “no-brainer” click on your site:

- Metadata – we’ve been using this to stand out in search results for years

- E.g. “free delivery” in title

- E.g. professionally written meta description copy

- Brand awareness/perception – think about whether you’d be likely to click on the Guardian or Forbes with similar articles for the same query

Optimising for rate of return to SERPs:

- Sitespeed – have you ever bailed on a slow site, especially on mobile?

- First impression – the “this isn’t what I expected” or “I can’t be bothered” factor

- Price

- Pop-ups etc.

- Aesthetics(!)

As I said, some of these can be daunting to approach as digital marketers, because they’re a little outside of our usual playbook. But actually, lots of stuff we do for other reasons ends up being very efficient for these metrics – for example, if you want to improve your site’s brand awareness, how about top of funnel SEO content, top of funnel social content, native advertising, display, or carefully tailored post-conversion email marketing? If you want to improve first impressions, how about starting with a Panda survey of you and your competitors?

Similarly, these KPIs can seem harder to measure than our traditional metrics, but this is another area where we’re better equipped than we sometimes think. We can track click-through rates in Google Search Console (although you’ll need to control for rankings & keyword make-up), we can track something resembling intent satisfaction via scroll tracking, and I’ve talked before about how to get started measuring brand awareness.

Some of this (perhaps frustratingly!) comes down to being “ready” to rank – if your product and customer experience is not up to scratch, no amount of SEO can save you from that in this new world, because Google is explicitly trying to give customers results that win on product and customer experience, not on SEO.

There’s also the intent piece – I think a lot of brands need to be readier than they are for some of their biggest head terms “going informational on them”. This means having great informational content in place and ready to go – and by that, I do not mean a quick blog post or a thinly veiled product page. Relatedly, I’d recommend this in-depth article about predicting and building for “latent intents” as a starting point.

Summary

I’ve tried in this article to summarise how I see the SEO game changing, and how I think we need to adapt. If you have two main takeaways, I’d like it to be those two KPIs – the speed with which users interact with a SERP, and the rate at which they quickly bounce back to results (lower is better) – and what they really mean for your marketing strategy.

What I don’t want you to take away is that I’m in any way undermining SEO fundamentals – links, on-page, or whatever else. That’s still how you qualify, how you get to a position where Google has any user signals from your site to start with. All that said, I know this is a controversial topic, and this post is heavily driven by my own experience, so I’d love to hear your thoughts!